Preventing Airplane Engine Explosions

We’ve seen it on the news multiple times — Engines exploding mid-flight on commercial aircraft, raining metal debris on anything and anyone below. The cause is often the same — fatigued fan blades hitting their last leg, snapping off and destroying the engine and its casing, while terrifying passengers on board. Some flights like United 328 out of Denver managed to land safely without passenger injuries, while others haven’t been so lucky. So why are these fan blades breaking apart and wreaking havoc on the skies, and are these incidents realistically preventable? In this episode, we speak to Reamonn Soto, CEO of Sensatek Propulsion Technology — an innovative startup creating fan blade sensors that grant an inside view into exactly what’s happening to an engine in real time, forwarding goals of putting these fan blade accidents behind us for good.

Credits

Interview with Reamonn L. Soto, CEO of Sensatek Propulsion Technology

Producers: Taylore Ratsep, Jolie Hales

Hosts: Jolie Hales, Ernest de Leon

Writer / Editor: Jolie Hales

Additional voices: James Hales

About Sensatek

Follow Sensatek

Forbes: From Zero To Mach 2 In Months – How HPC In The Cloud Helped Startup Sensatek Land An Air Force Contract

Referenced on the Podcast

Southwest Flight 1380 – April 17, 2018

Wall Street Journal – Report on Engine Failures

Turbine Accident Stats 2000-2016 – Full Report, Aviation International News

Episode Citations

- Tangel, Andrew; Sider, Alison. United’s Recent Engine Failure Spooked Denver. It’s Happened Before. The Wall Street Journal. March 19, 2021. https://www.wsj.com/articles/united-boeing-faa-jet-engine-cover-failure-11616159991 (Accessed May 1, 2021)

- Deerwester, Jayme. United Airlines engine failure: FAA orders airlines to perform thermal imaging on fan blades. USA Today. February 24, 2021. https://www.usatoday.com/story/travel/airline-news/2021/02/24/faa-emergency-airworthiness-directive-boeing-777-engine-fan-blades/4572420001/ (Accessed May 1, 2021)

- Gilbert, Gordon. Turbine accident stats 2000-2016: bizav accounts for more than half. Aviation International News. November 2017. https://www.livescience.com/49701-private-planes-safety.html (Accessed May 1, 2021)

- Pappas, Stephanie. Why Private Planes Are Nearly As Deadly As Cars. Live Science. 2018. https://www.livescience.com/49701-private-planes-safety.html (Accessed May 1, 2021)

- RAW: United Flight 328 engine catches fire. 9NEWS. February 20, 2021. https://youtu.be/sBxe4cQzUIY

- United Plane Showers Debris near Denver After Engine Failure. Bloomberg Quicktake: Now. February 21, 2021. https://youtu.be/mJBglRBa_Pk

- The Flawed Inspection Process Under Scrutiny in Boeing 777 Engine Failures | WSJ. Wall Street Journal. March 23, 2021. https://youtu.be/KEli6jXRlzI

- Pilot praised for landing plane after passenger sucked out of window | ITV News. ITV News. April 18, 2018. https://youtu.be/eRn9bqiixY0

- United Airline Flight 328 Pilots Called ‘Heroes’ For Actions After Engine Explosion. CBS Denver. February 22, 2021. https://youtu.be/vSxzWRcjIxM

- NTSB investigating United Airlines engine failure. Fox News. February 21, 2021. https://youtu.be/FupwI7RVgQ8

- United Flight 328: Dashcam video shows moment engine failed. 9NEWS. February 22, 2021. https://youtu.be/p1eVTMsAVug

- Hawaii couple recounts harrowing moments after United flight 328 engine explosion. KHON2 News. February 21, 2021. https://youtu.be/p1eVTMsAVug

- ‘It Was A Textbook Landing’: United Flight #328 Passenger Describes Engine Explosion. CBS Denver. February 20, 2021. https://youtu.be/Vj851Hihfmg

- US flight UA328 lands safely in Denver following engine failure. Al Jazeera English. February 20, 2021. https://youtu.be/vFy-JXrD6CI

- United Flight 328: NTSB says metal fatigue could have contributed to engine failure. 9NEWS. February 22, 2021. https://youtu.be/jIvD2eGZieQ

- NTSB Media Briefing on the investigation into united 328 engine incident. NTSBgov. February 22, 2021. https://youtu.be/-VfGJsfS13g

- Video shows moment debris from United Airlines plane falls onto Colorado street. Eyewitness News ABC7NY. February 21, 2021. https://youtu.be/5DJvOv8BsGg

- Debris from United Flight 328 || ViralHog. ViralHog. February 22, 2021. https://youtu.be/j2Xn4m_JlDI

- Boeing recommends grounding certain 777s after engine failure, falling debris. CBC News: The National. February 21, 2021. https://youtu.be/uC8V4Dnm6hM

- Boeing says all 777s with PW4000 engines grounded. CNA. February 22, 2021. https://youtu.be/0GVA5CpepZM

- United Airlines passengers brace for impact after engine cover rips off during flight. KHON2 News. February 13, 2018. https://youtu.be/J2kHchd6XHw

- Investigation Launched Into ‘Serious’ Air France Plane Engine Failure | NBC Nightly News. NBC News. October 1, 2017. https://youtu.be/-x753VXDeJ8

- Southwest Flight Makes Emergency Landing After Catastrophic Engine Failure Midair. ABC News. August 28, 2016. https://youtu.be/9uDvHq7fO_8

- Heroic crew of Southwest Flight 1380 describe bond that pulled them through chaos. CBS This Morning. May 23, 2018. https://youtu.be/l3b8g2HpAkc

- Passenger sitting near Jennifer Riordan talks about tragic flight. KOAT. April 26, 2018. https://youtu.be/T4-EE2hxPSQ

- Husband of woman killed on Southwest flight remembers their last conversation. ABC News. April 26, 2018. https://youtu.be/_mO0SQXRivg

- Passenger Livestreamed Video To Say Good-bye. Associated Press. April 18, 2018. https://youtu.be/kSasi87DYoQ

- How two pilots’ military backgrounds kept them calm during an in-flight emergency. ABC News. May 13, 2018. https://youtu.be/iiAW0kBqN8Q

Jolie Hales:

But just then, *explosion*… I’ll put an actual sound effect in there.

Ernest de Leon:

You should put that in, you really should. Boy, they can’t even afford real sound effects, they’re making it with their mouth.

Jolie Hales:

Whatever, that sounded exactly like an explosion.

Ernest de Leon:

Hey, this podcast is on a budget, you understand, a budget.

Jolie Hales:

Hi everyone, I’m Jolie Hales.

Ernest de Leon:

And I’m Ernest de Leon.

Jolie Hales:

And welcome to the Big Compute Podcast. Here we celebrate innovation in a world of virtually unlimited compute, and we do it one important story at a time. We talk about the stories behind scientists and engineers who are embracing the power of high performance computing to better the lives of all of us.

Ernest de Leon:

From the products we use every day to the technology of tomorrow, computational engineering plays a direct role in making it all happen, whether people know it or not.

Jolie Hales:

Hey Ernest.

Ernest de Leon:

Yeah.

Jolie Hales:

So I know that you’ve been on your share of flights in your lifetime, as I have for work and whatnot.

Ernest de Leon:

Far too many. For quite a few years, I was flying 50 plus times a year.

Jolie Hales:

Holy cow. That’s a lot.

Ernest de Leon:

It’s a lot.

Jolie Hales:

So you know that when you take a flight, it’s usually the same old thing. You wait, you board, you sit uncomfortably close to people you don’t know, you wait, you fly, you wait, deplane, the end. Right?

Ernest de Leon:

It’s beautiful, yes.

Jolie Hales:

So when something out of the ordinary happens on a flight, it’s usually, I think, safe to say that it’s pretty memorable, because it breaks up the norm.

Ernest de Leon:

Yeah, I would agree with that.

Jolie Hales:

For instance, I remember flying out of John Wayne Airport in Orange County one time and because that airport is in the heart of suburban communities, they have this noise ordinance that requires aircraft to take off and increase altitude at this incredibly steep angle. This steep angle climb from John Wayne Airport prevents the loud sound of the aircraft, basically, from lingering too long or too loudly in the neighborhoods below, so that’s why it has the steep takeoff. And I remember one time I was on a Southwest flight actually, taking off from this airport and as the airplane was tilted nose up in this steep climb, this flight attendant at the front of the plane, got on the intercom and said.

Flight Attendant:

This is a short flight and I’m a lazy flight attendant, so grab what you want.

Jolie Hales:

And then he proceeded to dump a box full of snacks out at the top of the aisle and then these snacks were tumbling down the slope and people in the aisle seats were reaching out and scrambling to pick up whatever potato chips or pretzels slid by them like they were on this playground slide. I have never seen anything like that happen, it was so funny to me, I was laughing my head off because it was out of the ordinary, it was out of the norm on a flight when flights are typically the same old thing. And I mean, that flight attendant has no idea, but I will never forget how funny that experience was on that airplane.

Ernest de Leon:

The pre-COVID days. Could you imagine them dumping snacks down the floor in a COVID world?

Jolie Hales:

Hopefully the snack dumping days will come back.

Ernest de Leon:

Yeah. People would be like, “I am not touching that,” but yeah, that’s a good story, I love flight attendants. They’re often hilarious despite having to deal with morons on a daily basis. I see the abuse that they have to go through from customers that just don’t want to listen and don’t want to behave, and I feel bad for them, but they do it with a smile and they’re some of the most professional of professionals I’ve ever encountered in my just day-to-day life.

Jolie Hales:

Yeah, I agree. Well, usually… I’ve run into the jaded flight attendant that puts the smile on, but their eyes look like they want to throw daggers at you.

Ernest de Leon:

Yeah. Those are the ones that had the person on the previous flight that just did not want to behave.

Jolie Hales:

Yeah, exactly. You never know what they went through just before they encountered you. So it’s good to give them the benefit of the doubt.

Ernest de Leon:

I am always nice to them because I also know that-

Jolie Hales:

You have to be or else your flight is miserable.

Ernest de Leon:

Yeah, but you often get upgrades, too, if you’re nice and everyone else is being not nice and there’s an open seat in first class, the flight attendant will be like, “Come here, follow me.” So be nice, it gets you further.

Jolie Hales:

I like that. So that particular flight attendant and that particular flight for me was memorable in a good way. And fortunately, other than some, maybe pretty rough landings, especially at John Wayne Airport, and I’ve had a few delayed or canceled flights and I’ve even had stuff stolen out of my luggage. That’s happened to me twice — on two separate occasions. But other than that I, knock on wood, have never actually had a flight experience that was memorable because something went dramatically wrong, at least not in midair. I’ve never had to use the oxygen masks or even had to be diverted to another airport mid-flight. I mean, have you experienced anything like that?

Ernest de Leon:

Not on US or European airlines, but ironically enough, I did take a value airline in Mexico and I can’t say this for sure, but it looked like this company was getting all of the old airplanes at Southwest that the other were no longer using, and they stripped everything out and they left the seats, but all the stuff you normally would see in there, like the carpeting on the floor, that was gone, it was replaced by this rubber sheet. And then the walls had all the other stuff stripped off. It was pretty bad, but the flights were super cheap. And we did have a scenario on there where the meteorological radar broke during takeoff. Okay, so the pilot makes an announcement shortly after takeoff. We’re still ascending, right? And says, “The meteorological radar has broken, we’re trying to decide what to do, just hang tight.” And a couple of minutes later, he comes back on and says, “We’ve decided to just go ahead and continue the flight.” And that was it. That’s all he said. And I don’t know if you know what the meteorological radar does, but well-

Jolie Hales:

As a pilot, isn’t that essential? I don’t know.

Ernest de Leon:

What it’s doing is it’s looking for meteorological phenomenon so the pilot can avoid them. Like a rough turbulence and things like that.

Jolie Hales:

Like a tornado.

Ernest de Leon:

Right. So this pilot decided it doesn’t matter, it broke, we’re going to go anyway. And man, that was an interesting experience because we must’ve hit every kind of turbulence on that flight because he couldn’t see, right? He couldn’t see it. So yeah.

Jolie Hales:

That’s terrifying, and why would you tell the passengers? I don’t know if I’d want to know that. If I heard a pilot get on there and be like, “So we have this scenario where meteorological radar broke and we’re trying to decide what to do.” I’d be like, “Turn around, I don’t know what that means, but time to go back to the airport.”

Ernest de Leon:

Exactly. And I was on this plane with one of my college dorm mates and I looked over at him and I said, “I don’t think we’re going to make it.” Obviously we made it because I’m talking to you now, but yeah, that was-

Jolie Hales:

What a trip.

Ernest de Leon:

As you mentioned, I will never forget it.

Jolie Hales:

But I’m glad that you haven’t been through anything mid-flight, that’s worse than that.

Ernest de Leon:

Any major ones, yeah.

Jolie Hales:

Nothing that’s a headline the next day, right?

Ernest de Leon:

That’s right, that’s right.

Jolie Hales:

Because I mean, let’s be honest — I imagine that having something go wrong in the air mid-flight would be an incredibly scary experience because you literally have no control over the situation as a passenger. And all you can do if something goes wrong is sit in one place and basically just pray that things will be all right. And not too long ago in February of 2021, something went wrong on a commercial flight that made the headlines and some of our listeners might remember this, but of course this is a good moment for us to paint a picture of the scene and what it was like to be there.

Flight Attendant:

Ladies and gentlemen… [chatter]

Jolie Hales:

So imagine, you board a flight at the Denver Airport, about an hour’s drive from your house, we’ll say. Your cousin is getting married in Hawaii and there is no way that you’re going to miss the excuse to visit a tropical paradise in the middle of Colorado’s cold months. So you take your assigned seat by the window, just behind the wing, and you watch the conveyor belt outside load your brightly labeled luggage into the plane. That’s a good thing, because at least now you know that your wedding clothes will make it to the same location.

Ernest de Leon:

I would never trust wedding clothes in checked luggage. Those would be coming as carry on for me for sure.

Jolie Hales:

Well, that’s probably a good idea, but I’m always carrying some big drone with me as my carry on, so I would probably have to chance it.

Ernest de Leon:

Not having your wedding clothes wherever you land is a big problem. Especially if you are the bride or groom.

Jolie Hales:

Well, if you’re the bride or groom, yeah. You’re not going to just pack your wedding dress for sure. But I digress, back to our story. So you’re seated on this flight and you’re waiting for others to store their overhead bags and find their seats, so you kick back. You’re ready to relax, or at least you’re ready to relax as much as possible in a metal tube crammed with 228 other passengers. And you barely pay attention to the flight attendant safety demonstration in the aisle that you’ve seen so many times before. Eventually the aircraft takes off smoothly and you’re well on your way to Hawaii. You lazily gaze out the window and watch the landscape below become more distant, envisioning the Hawaiian paradise you’ll see in just a few hours. Four minutes of gradual climbing go by until the chime dings signifying the steepest part of the climb is over. Seems like as good a time as any to take a nap, so you close the window shade and start to settle into your seat. But just then…

[explosion]

Jolie Hales:

You sit up straight. What was that? You pull up the window shade and look outside and it takes a moment for you to grasp what you see. The airplane’s engine on the wing outside your window is on fire, smoke billowing from the back. Not only that, but the engine casing appears to be completely missing and the rickety metal left behind is vibrating back and forth, shaking the entire plane. You quickly scan the airplane for flight attendants. Other passengers on the same side of the aircraft are also looking out the window and the chatter increases. The woman in the seat next to you is staring out the window with wide eyes. After a few moments, the pilot’s voice comes on the intercom, calmly stating that they’re going to turn around and land back in Denver. The woman beside you pulls out her phone and types with shaking hands, pausing to wipe away tears. You grip the arm rest under the window, this is going to be the longest landing of your life… The good news is, United Flight 328 did land safely. So while many people on that plane were sending their last goodbyes to loved ones on the ground, everything thankfully turned out all right in the end.

Passenger:

When the pilot landed, it was the textbook landing. If we could have stood up, we would have given him a standing ovation when we landed.

News Clip:

Once back on the ground, fire trucks sprayed foam on the engine to extinguish the fire and passengers were allowed to disembark.

Passenger:

I’m happy to be down here alive, so it’s just like anything, count your blessings.

Ernest de Leon:

So do they know what happened?

Jolie Hales:

Well, an investigation was conducted quite quickly, as you might imagine, and this is how chairman of the national transportation safety board, Robert Sumwalt, explained their findings.

Robert Sumwalt:

This engine, which is a Pratt & Whitney 4077, has 22 fan blades. And the fan of blades are what, if you were to look immediately into the front of the engine, those are the blades that you would see, all of these connect into the hub. Two fan blades were found fractured, one fan blade fractured at the root, which is where it joins into the hub and the other adjacent blade was fractured at about mid span. Now, one of the fan blades was found embedded in the engine containment ring in about the one o’clock position of the engine, if you were to look into it from the front. Another small piece of a fan blade was recovered on a soccer field in Broomfield.

Ernest de Leon:

Did he say that pieces of the engine were found in soccer field?

Jolie Hales:

Yeah, but thankfully it was a chilly day, I think it was around the 40s or something, and I don’t think anyone was actually using the soccer field at the time, thank goodness. But I mean, imagine it, while there were people in the airplane who were terrified of being able to land safely, others on the ground in the suburbs were seeing this debris suddenly fall from the sky and then smash into whatever was below.

Ground Witness:

Hey, can you grab Josie?

Ground Witness:

Why?

Ground Witness:

So that she doesn’t get hit by something.

Ground Witness:

It’s got a blown engine. Oh, no.

News Clip:

Huge pieces of metal seem falling from the sky.

News Clip:

When the debris comes out of the engine, that hot metal falls on the ground, can be very dangerous. Very, very fortunate that no one was hurt.

Jolie Hales:

Some debris hit the roof of a house and went right through the ceiling, and we’re not just talking small debris. There’s this picture for instance, of the entire outer ring of the front of this engine casing. And it’s just sitting in the front yard of some house against a tree, and this thing is bigger than the big pickup truck that’s parked right next to it.

Ernest de Leon:

Yeah. Those things are massive.

Witness:

We looked out the front window and this gray big piece just rolled right past the front window and went up against the tree. I didn’t know that the pane was going to make it, I thought the plane would actually crash.

Ernest de Leon:

So what caused this engine blade to fracture?

Robert Sumwalt:

A preliminary on-scene exam indicate damage consistent with metal fatigue.

Ernest de Leon:

Oh, fatigue. So, that means the metal must have just received its second COVID vaccine injection.

Jolie Hales:

Oh my gosh.

Ernest de Leon:

That’s so good.

Jolie Hales:

Oh wow, that was actually really clever, I’m going to murder you. But as for this failed aircraft engine, it was 26 years old, which is apparently on the older end of the turbine engine spectrum. And yeah, they think that one fan blade was particularly worn out and then it broke apart and hit another fan blade that then busted the whole engine casing apart and caused debris to rain down on the neighborhoods below. So as far as the fire goes though, because it caught fire after that, it’s interesting because the fuel was actually turned off on that engine after the explosion, so investigators were a bit confused as to why the engine was still on fire and I wasn’t able to find anything conclusive online. There’s probably an answer by now on that.

Ernest de Leon:

Yeah. I mean, my only assumption is there are a lot of parts inside the engine that can still burn even if there’s no fuel, especially at very high temperatures. So these are probably things that were just still burning from the earlier-

Jolie Hales:

From the initial explosion.

Ernest de Leon:

From the initial explosion, yeah.

Jolie Hales:

Yeah. It must’ve been something like that. And as you might imagine, having this engine basically explode in midair, I mean, this event had repercussions.

News Clip:

Boeing setting recommends suspending the use of all 777s with the same Pratt & Whitney 4,000 series engine until the US federal aviation administration comes up with an inspection protocol. The recommendation comes just hours after United grounded its fleet.

Jolie Hales:

A few days after the incident, the FAA issued what’s called an emergency airworthiness directive, which ordered US airlines to closely inspect any aircraft using this specific PW 4000 engine, which I guess is typical to Boeing 777s that were primarily used by United Airlines in the United States. Though Japan and Korea also use those engines on some of their planes, and so they also grounded a number of their planes for their own inspections.

News Clip:

More than 120 triple seven jets around the world have been grounded.

Jolie Hales:

The FAA inspection was ordered to be conducted through thermal acoustic image technology, which is supposed to be able to detect cracks on the interior surfaces of hollow fan blades in areas that basically can’t be seen in a visual inspection.

Ernest de Leon:

Right.

WSJ video:

The fan blades are hit with sound waves that cause the structure to subtly vibrate. If there’s a crack somewhere in the interior of the fan blade, the vibration will cause friction and therefore heat, which an inspector’s instruments can detect on the fan blade surface.

Ernest de Leon:

This isn’t the only incident where a fan blade has given out and broken the engine of a commercial aircraft mid flight though.

Jolie Hales:

You are correct. So United 328 in Denver is just the most recent incident as of this recording. In December of 2020, another Boeing 777 near Japan, experienced a similar two fan blade break shortly after takeoff, which caused the outer engine cover to break apart and then fall into the ocean below. And fortunately again in that case, the plane was able to safely land. And many people will remember the sad story of Southwest flight 1380, from LaGuardia to Dallas in April of 2018, which was a different aircraft but a very similar scenario.

Southwest 1380 Pilot:

Yeah, we have a part of the aircraft but you’re still going to need to slow down a bit. Could you have the medical meet us there on the runway as well? We’ve got injured passengers.

Air Traffic Control:

Injured passengers, okay, and is your airplane physically on fire?

Southwest 1380 Pilot:

No, it’s not a fire, but part of it is missing.

Jolie Hales:

Apparently a fan blade broke, hit the engine cover which then basically shattered apart, but in that case, the debris also crashed into one of the planes windows and sadly killed a passenger.

Southwest 1380 Pilot:

They said there was a hole and someone went out.

Air Traffic Control:

I’m sorry, you said there was a hole and somebody went out?

News Clip:

Flight 1380’s crew has been widely commended, along with the skill and calmness of pilot, Tammie Jo Shults.

Jolie Hales:

Two months before that, another Boeing 777 flight to Honolulu had a fan blade break due to fatigue, and then it busted up the engine cover over the ocean-

News Clip:

About 40 minutes before they were about to land, the cover fell off one of the engines.

Jolie Hales:

And it threw the plane’s aerodynamics out of whack, making the pilot… he said it felt like a barn door had been opened on one side of the plane.

Pilot:

It felt like we hit a brick wall at 500 miles an hour.

Jolie Hales:

And he was over the ocean, so he still had quite a distance to fly after that. And so he really had to use his skills as a good pilot to land that plane safely after the full flight.

WSJ video:

In the 2018 incident, the National Transportation Safety Board or NTSB, found that flawed inspections were the root cause.

Jolie Hales:

In 2017, an Airbus A380 was flying over Greenland when the engine burst apart.

News Clip:

Flight 66, Paris to Los Angeles with 520 passengers and crew was over the Atlantic, South of Greenland when passengers say the engine seemingly exploded. Experts speculate a cracked engine fan blade may have come apart in flight causing the engine to disintegrate.

Jolie Hales:

And in August of 2016, a Southwest flight from new Orleans to Orlando, made an emergency landing after one of its 24 fan blades broke, again, due to fatigue.

News Clip:

An engine on the Southwest flight blew apart and shrapnel may have penetrated the cabin itself.

News Clip:

This was an explosive event with this engine and it put hot metal into the cabin, therefore losing the cabin pressurization, the masks drop down and people are having to get on oxygen masks.

Jolie Hales:

Now while it is important to stress that these incidents are rare and commercial flight is statistically very safe, These fan blade failures have happened on multiple occasions. And that’s why I wanted to talk to this guy.

Reamonn Soto:

When I hear of an issue like that, that I feel like could have been prevented or could have been better managed, it’s hard not to feel a little upset about that.

Jolie Hales:

That’s Reamonn Soto, CEO of Sensatek Propulsion Technology.

Reamonn Soto:

But it also gives you a sense of purpose to let you know like, “Hey, what we’re doing is in fact going to save the world.”

Jolie Hales:

Reamonn and his team are working on technology designed to prevent exactly these kinds of incidents.

Reamonn Soto:

We are innovators in passive-RF sensing technology for extreme environments. And basically, in a nutshell, we develop technology that tells when big engines get too hot.

Jolie Hales:

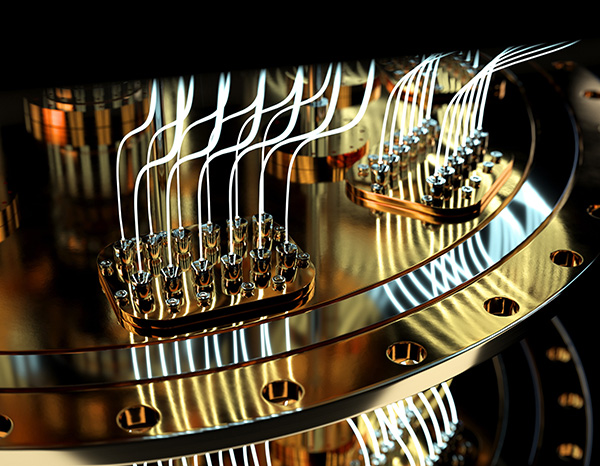

Basically Reamonn’s company, Sensatek, has created this sensor the size of a fingernail, that can be embedded on a turbine jet engine blade and offer real time temperature and pressure data to the user, and they’re testing sensors that can also measure strain and vibration.

Ernest de Leon:

It’s like the IoT of the jet engine world.

Jolie Hales:

Yeah, that’s a good way to look at it.

Reamonn Soto:

Our product line consists of ultra high temperature sensors that can go as high as 2000 degrees centigrade wirelessly, and then high temperature pressure sensor, second since pressure, at temperatures as high as almost 2000 degrees centigrade as well.

Jolie Hales:

Sensatek’s system basically pings the blade sensors with energy and the sensor then radiates it back to a tiny antenna, allowing the system to track those signals and measure temperature and strain, that’s basically how it works. And without this kind of new sensor technology, there really isn’t a way to know exactly how hot an engine gets nor how long an engine stays that hot, let alone any real data directing how that impacts and engines lifespan or long-term performance. We just don’t have a lot of that information. Conversely, if you’re able to see that kind of data in real time, you can start to get a sense for how far you can push an engine before it becomes risky or a safety hazard to keep using it.

Reamonn Soto:

I’m confident knowing that blades aren’t going to just come off because I now have a more accurate picture of what’s happening.

Jolie Hales:

In fact, one of the contracts Sensatek has landed is with the US air force. A particular project they’re working on, is concerning this fleet of business jets that have now been repurposed to do military missions, like fly over Afghanistan or Iraq to create Wi-Fi in the sky. But business jets were originally developed to make flights from LA to New York, and now suddenly they’re being taxed in this different way, flying through sand and ash in different temperatures for different durations.

Reamonn Soto:

We then help them on the ground, come up with, “Hey, this is what’s happening on your core critical components inside of the engine.” We’re putting these chips directly on parts that are super high temperature, spinning at very fast speeds, very aggressive, and now we’re helping them know how aggressive can you really get with this, and is this the right plane for this mission or should we use this other plane for this mission? And so it becomes this big fleet management tool.

Jolie Hales:

And it’s really no shock that Reamonn would be doing what he can to lend a hand to the US armed forces, given that he was a Marine himself.

Reamonn Soto:

One of the things that really made me want to aspire to be a Marine was that they were really boots on the ground, first to be called up into action and I wanted that dose of leadership — I wanted that fire and I certainly got it. But I also wanted to fulfill a promise that I had made to my mother who was big on education and ensured her that I was going to reserves and go to college.

Ernest de Leon:

And I’m sure she’s incredibly proud of her son.

Jolie Hales:

She must be, man. He’s cool.

Ernest de Leon:

Yeah, he’s definitely an accomplished individual and bringing something to the market that is in dire need.

Reamonn Soto:

After going to the Marine Corps, I felt that I was not afraid to do anything. I did fulfill the promise to my mother to go back to school and I chose the hardest degree I thought was possible, that would challenge me the most.

Jolie Hales:

Really?

Reamonn Soto:

And that was pursuing a bachelor’s degree in physics. And I would regret that decision every class I had to take, but I thought that school more or less gives you the skill of learning how to learn, and I thought that if I could learn how to learn physics, I can apply that skill to just about anything. But for grad school, I decided to do something I thought was a little bit more practical, something that was more me, so I went into aeronautics and that’s what led me into learning about the problems associated with jet engines and really pursuing a lifelong dream that I had as a kid in wanting to be in aerospace.

Jolie Hales:

And it was through his graduate research on jet engines and working in the gas turbine lab that he started to notice engine components constantly overheating and then being destroyed. And beyond the jet engines in the lab experiencing trouble, the energy utility company even, that provided power to their lab also just happened to be using that exact same kind of jet engine to generate power, which I will be honest, I have never really considered before. I mean yeah, we know that jet engines are used in aerospace, but I did not think about them as being regularly used to create power in a utility.

Ernest de Leon:

Yeah. I mean, we’ve all heard of hydroelectric power and those are turbines that are being used but they’re having water pushed through them instead of air. So we know about those, but I’ve also never heard of jet engines being used to produce electricity.

Jolie Hales:

Yeah. Apparently it’s a thing, and he saw this utility trying to generate power with this jet engine that also overheated, and then it costs millions of dollars to replace the components.

Reamonn Soto:

I’ve learned that this was actually a common thing, this was a trend that was happening.

Ernest de Leon:

Yeah. I had imagined that it is pretty common, because a lot of these things they’re tested during what they consider normal operating conditions and then they’ll push it to failure, and they’ll mark where that failure point is and then try to gauge where the middle of that is and make that the normal operating range, but things degrade over time.

Jolie Hales:

And that’s just relying on historical information.

Ernest de Leon:

Right, it’s nothing current or looking at the future, it’s just, “Hey, when we have this engine in the lab, this is where you could run it and this is where it failed, so stay away from that failure point.” But again, those were probably brand new parts. And over time, things degrade and things change and this is where Reamonn’s technology comes into play because they can give you real time analysis of all those different metrics.

Jolie Hales:

Yes, exactly. So Reamonn was seeing this happen in this lab, and so he started to talk to more people to see if this was something that others had experienced as well. And he was surprised how many jet engines were being used at power utilities across the United States. And he was also surprised how many of them were experiencing these overheating issues, likely because they were being utilized differently than they had been originally designed for. I mean, these jet engines had originally been designed to go in a jet.

Ernest de Leon:

Yeah. I would imagine that part of the problem is that in normal operation, they’re very high up in the atmosphere pulling in very cold air.

Jolie Hales:

Yeah. That’s probably part of it. Also you’re going to fly for a few hours at a time, right?.

Ernest de Leon:

Right. And they’re typically generating most of their thrust on takeoff and then leveling off and not using as much power. So yeah, it’s definitely-

Jolie Hales:

Different.

Ernest de Leon:

Yeah.

Jolie Hales:

It’s being utilized in a different way. And so Reamonn saw this and then he came up with this idea to create a sensor, small enough to embed on a single turbine blade without affecting its performance. And then it would have the ability to wirelessly record real-time temperature data in previously ridiculous levels of heat. So this hasn’t been done before, and so now he works with big equipment manufacturers to get more of these sensors onto engines across aerospace, but also across power utility companies who use these engines, giving these users data that can then be plugged into an AI predictive model that could then notify when an engine should be taken offline for maintenance before they go down or worse, break in the middle of, let’s say, a flight.

Ernest de Leon:

Right. And this type of technology could have prevented some of the turbine blade failures on commercial airlines that we talked about.

Jolie Hales:

And each time Reamonn hears about one of those stories on the news, he told me that he can’t help but be a little bit, frankly, upset. And at the same time, feel this incredible amount of resolve.

Reamonn Soto:

My first thought was, “This isn’t cool.” There are some things that you just expect to happen every time, like aircraft engines, they can’t fail.

Ernest de Leon:

I agree with him. As an engineer, anytime you hear something like this, the first thing that comes to mind, of course, aside from the tragedy aspect of it, is what can we do to prevent this or fix this? And that’s just how engineers think. So I can see how Reamonn became upset but then immediately pivoted to, “How do I fix this, how do I solve this?”

Jolie Hales:

And that’s exactly what he thought. And as a fast growing startup, Sensatek has been reaching out directly to engine makers to let them know that they even have this technology, that this technology exists. In fact, on one occasion when one of these commercial flight engine blade failures hit the news, Reamonn’s team reached out to all the CEOs of the largest engine makers to remind them, “Hey, we can help with this. We have this technology that can prevent this.” And when I hear Reamonn talk about it, it makes me feel like the people at Sensatek really are driven by principle and the desire to fix this problem more than necessarily just a pocketbook issue, if that makes sense. They’re in a business but I feel like they’re also in the business of helping people and they know that.

Ernest de Leon:

Right, and that’s actually the right way to do it. If you get the engineering right, if you build around principle, the pocketbook thing will solve itself.

Reamonn Soto:

You become more relentless when you’re now dealing with the engine makers. It’s like look, I have more of a conviction to send more emails to those guys, to call them up and be relentless in our approach to say, “Look, let me get this in front of them.” The sense I get is, “Hey, current technology may be good enough, but is that what you tell the lady’s family who lost her life in 2018?”

Jolie Hales:

From supersonic jets to personalized medicine, industry leaders are turning to Rescale to power science and engineering breakthroughs. Rescale is a full stack automation solution for hybrid cloud that helps IT and HPC leaders deliver intelligent computing as a service and enables the enterprise transformation to digital R&D. As a proud sponsor of the Big Compute Podcast, Rescale would especially like to say thank you to all the scientists and engineers out there who are working to make a difference for all of us. Rescale, intelligent computing for digital R&D. Learn more at rescale.com/bcpodcast.

Ernest de Leon:

Yeah. I completely get it — breaking into a market, getting your message out there is very hard. Once you’re in the market and you’re recognized, it’s easy at that point, but Sensatek is trying to grow and trying to show what it has to the market and it’s hard. So all of this stuff we’ve heard from Sensatek and the technology and how it works is amazing. But the question I think our listeners have is where does high performance computing come into play in all of this?

Jolie Hales:

Well, I’m glad you asked because obviously we have to talk about that tie-in. So Sensatek’s technology is constantly evolving to custom fit different blades, different engines, different systems, I mean, whatever is needed by the industries they serve and developing a sensor as you might imagine, that can deliver on its promise while not melting down in extreme temperatures, takes a great deal of-

Ernest de Leon:

Computational simulation.

Jolie Hales:

Yeah. So they’re running simulations of each component of the sensor design to get the best product made with the best components and materials and at the best size, because the size and the materials do matter, you don’t want to build something that’s going to throw off the engine itself, right?

Reamonn Soto:

Right. One of the things I’ve learned just from my background in the Marine Corps, how leadership is the ability to achieve purpose through uncertainty, so we’re looking at ways in how we do that.

Jolie Hales:

Reamonn’s team originally tried running their computational simulations on a desktop system. But as simple simulation was just taking way too long.

Reamonn Soto:

Assuming that we don’t have errors or your computer doesn’t crash because you got the core speed but you don’t have the memory, and you didn’t know until halfway through your simulation. I would say it still took us a week.

Jolie Hales:

They also considered setting up their own on-prem system, but after considering all their options, they decided to go with Rescale. And just as full disclosure, Rescale is a sponsor of this podcast, and without making this a Rescale advertisement, I think it does make sense to explain for those who aren’t familiar with Rescale, that Rescale is basically this platform that allows the user to run high performance computing jobs on, I mean, just about any software or any cloud or hybrid system in a way that’s optimized for either cost or speed or performance or whatever. I mean, the user basically sets the parameters and then just hits go.

Reamonn Soto:

Even if you have a powerful workstation, you’re probably still going really slowly. I thought that was great, I mean, I was happy with taking a week waiting on a simulation result. And now we can get simulation results within an hour.

Jolie Hales:

We had Rescale pull the numbers, and it looks like Sensatek has run a total of 124,239 core hours on the Rescale platform, which Sensatek says has allowed them to run a job, go grab a cup of coffee and come back a few minutes later to see the results instead of waiting a week or two, like they did before when they were just using their desktop systems.

Ernest de Leon:

That’s pretty amazing but I will say they’re slacking a bit, because I know people who have put more than 124,000 hours into Animal Crossing.

Jolie Hales:

Oh my gosh. Has Animal Crossing been around for that many hours?

Ernest de Leon:

No, I don’t think. Well, not the newest one but-

Jolie Hales:

Convert hours to days, we’re going to do this math right now.

Ernest de Leon:

Yeah, 124,239.

Jolie Hales:

5,176 days. I don’t think even the original Animal Crossing has been around that long, has it?

Ernest de Leon:

5,000, that would be over 10 years?

Jolie Hales:

Let’s see, convert hours to years. This is very important for us to know. Okay, 14 years.

Ernest de Leon:

September 16th, 2002 was the first release of animal crossing. So it’s possible.

Jolie Hales:

So somebody could have put that many hours…

Ernest de Leon:

Yeah.

Jolie Hales:

Yeah, I know people who lived on that, especially the first few months of the pandemic. I was on it myself for a little while and then at this certain point I just couldn’t do it anymore.

Ernest de Leon:

Yeah. Those kinds of games just starting to validate is not for me, because you’re burning time and time is something I just-

Jolie Hales:

Yeah. You’re not meeting a goal and it never ends.

Ernest de Leon:

Yeah, yeah.

Reamonn Soto:

And there’s nothing like testing something and the result is spot on from what you got in the simulation. And so that further then builds trust in our process and the tools that we use.

Ernest de Leon:

Absolutely. And trying to get all these different groups and people with different disciplines and skill sets to collaborate on these, is a lot more difficult outside of the cloud HPC context. So being able to collaborate on a platform that is in the cloud so that your members can be anywhere at any time using it, really helps increase the efficiency of your groups, of just your engineering groups in general, but also drastically decreases the cost versus trying to maintain an on-prem system.

Jolie Hales:

Yeah. And that’s interesting you should say that because Reamonn has talked about how sometimes their engineers are in separate states, a lot of people are working remote during the pandemic and all that and this has made it easy for them to be able to collaborate because they can just access everything on the cloud. In fact, they showed me a picture of their CTO that showed him “using Rescale” and he was literally standing knee deep in an ocean, just off the beach on his laptop.

Ernest de Leon:

That’s a life of a startup you’re working from anywhere, anytime, just trying to get things out the door.

Jolie Hales:

And I thought this was interesting. When I asked where else Reamonn would like to see these sensors installed outside of jet engines, he responded–

Reamonn Soto:

I would love to see sensors applied in turboprops. You see more planes with turboprop engines that have resulted in fatalities than you do with jet engines. It’s like the turboprop planes, those are the ones that don’t really get a lot of love. Everyone likes to be a jet setter. You think of jet engines, you think of the private jet lifestyle or you think of that feeling when you’re on a Delta flight or you feel like you’re going places. But when you’re on a turboprop, it’s like, “Oh, man.” That’s like the Greyhound bus of the skies, right?

Jolie Hales:

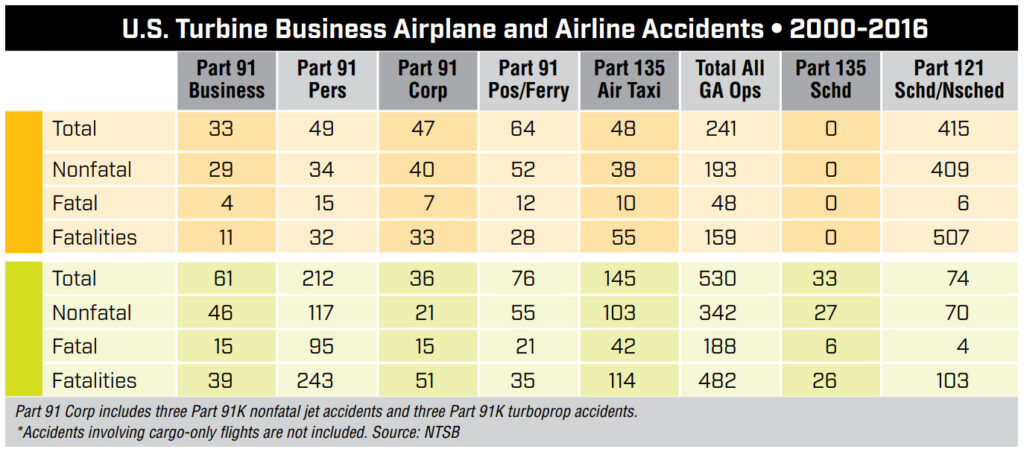

And this got me down the rabbit hole on safety statistics across transportation. And I found some NTSB data that I’ll link to in the episode notes, that says that between the year 2000 to 2016, turboprops accounted for 70% of all US turbine business airplane accidents, which totaled around 530 accidents over the 17 years. And statistics show that there were three times more turboprop accidents than jet crashes, even though turboprops fly many thousands less hours each year than jets.

Ernest de Leon:

Absolutely. And it’s like I told Reamonn, I’ve flown quite a few of those puddle hoppers in the past and-

Jolie Hales:

Oh, they’re scary. I never feel like I’m going to survive.

Ernest de Leon:

They are definitely… how did I phrase it, that when you’re in a big jet like a 747 or a triple seven, you feel like you own the sky. When you’re in a turboprop, you feel like the sky owns you.

Jolie Hales:

It’s true. I took one in Guatemala and I was like, “Well, I guess this is how I die.”

Ernest de Leon:

Yeah. I took one between two of the Hawaiian islands, and even that short trip I was like, “Oh man, I do not like this thing.”

Jolie Hales:

Yeah. I was excited when the landing gear had touched ground the way it’s supposed to.

Reamonn Soto:

And so we want to be on those. I feel like that’s where we could really make people feel safer when traveling.

Jolie Hales:

And when it comes to statistics about accident fatalities in general, I mean, we’ve all heard that flying in a commercial jet is probably safer than driving a car, but when it comes to the fatality rate by hours traveled, it’s actually apparently 19 times more dangerous to get into a private plane than it is to get into the family car. And much of that isn’t thanks to these turboprops, apparently, which I really wasn’t aware of but it makes sense now that I’m looking at the statistics. And while engine fatigue and failure may not be the cause for all of these accidents, it must be a contributor in some.

Ernest de Leon:

Absolutely. And with this kind of data, you can easily see that there is quite a market here for Sensatek to make a difference.

Jolie Hales:

Right. And I know that if I was flying in a plane and I knew that whoever was maintaining the engine had been tracking it with sensors and making sure that the engine wasn’t fatigued, I mean, that would be another step in the safety comfort zone for me. And not that people should be terrified every time they step onto an airplane or a turboprop plane even. Too bad we can’t put sensors on every driver on the road to tip us off on who is the highest risk behind the wheel.

Ernest de Leon:

Oh, that’s coming, that’s coming, believe you me.

Jolie Hales:

One can only hope. So I asked Reamonn if he ever sees a day in the future, realistically, where their sensors could be used as a typical integrated part of turbine engine blades, if they would be universally adopted and he said, “Yeah, absolutely.” That’s what he wants. And he says that the key will be working closely with these large OEMs, which by the way, stands for original equipment manufacturer, companies like GE or Vestas or SGRE.

Reamonn Soto:

We can just spend 24 hours a day just really getting the capability integrated using the brains, the expertise, the capabilities, the market channels and the structure that the OEM has so that we can get this capability and save lives as fast as possible.

Jolie Hales:

And while they can’t speak publicly about company names yet, Sensatek is already doing active demonstrations with a number of big OEMs, but there are still others who have yet to jump on board.

Reamonn Soto:

There are a lot of engines, and so the most important thing is getting the capability out there and helping save lives, helping to push the boundaries of innovation, but being able to do that with your eyes open.

Ernest de Leon:

That’s absolutely true. So bringing innovation into the realm of safety is critical for all of us, I think, and turbine blade engine sensors are just one innovation made possible through access to virtually unlimited compute.

Jolie Hales:

It’s true and well, that’s going to do it for this episode of the Big Compute Podcast.

Ernest de Leon:

If you want to help spread the word, you can leave us a five-star review wherever you get your podcasts, like Apple Podcasts.

Jolie Hales:

Or Google Podcasts.

Ernest de Leon:

Or Google Podcasts.

Jolie Hales:

Or Spotify-

Ernest de Leon:

Or Spotify, now.

Jolie Hales:

And even more than that. Go ahead and tell a friend about us. If you know somebody who might find this podcast interesting, people like us really rely on word of mouth.

Ernest de Leon:

Yep. And don’t forget, you can tweet us.

Jolie Hales:

Oh, yeah. Tweet Ernest, because I’m never on Twitter. Thanks for listening, stay safe.

Ernest de Leon:

Goodbye. When you call on an automated line and you’re not putting in the options that it wants to hear and it’s like “Goodbye.” Then it hangs up the phone, that’s what that was.